It was in 1977-78 when around five

Muslim brothers working for the PNG

government, statutory bodies and the

University of Papua New Guinea

decided to meet weekly to pray in

Jam’ah, at least for one Salah. They

picked Maghrib Salah on Fridays.

After a few months it was decided

that Jum’ah prayer would take place

in the home of one of the brothers

at the University campus, instead.

After a few months a request was

made by the Indonesian Ambassador –

Brother Buseri, who later became

Governor of Irian Jaya in 1981/82 –

to shift Friday prayer at his

residence as he was unable to attend

it at the University campus, since

the relations between the two

countries were not pleasant. Thus

Friday prayer was transferred to his

residence. I do not know the exact

date or year as it happened before

my arrival in the country. I was

informed by Brother Ilteja Hussain

of Agra, India who was an Associate

Professor with the Department of

Politics, after my arrival in April

1980. Dr Ilteja Hussain left the

University in early 1981.

It was possibly between 1979 and

1980 when RISEAP – Regional Islamic

Da’wah Council of South East Asia

and Pacific – was formed and Dr.

Qazi Ashfaq Ahmad, an Associate

Professor of Mechanical Engineering

with the University of Technology,

Lae, became its member and one of

its vice presidents. At that time he

founded Islamic Society of Papua New

Guinea (ISPNG) in Lae with two other

Muslim brothers –Dr. Abdullah Gurnah

from Zanjebar (Tanzania) and an Arab

brother whose name has escaped my

memory. It was in early 1981 that

Dr. Qazi Ashfaq asked us – the

Muslim brothers in Port Moresby (POM)

– to form an Islamic Society as the

one they were running was not very

active since there were only three

Muslims in Lae.

|

First two Papua New Guineans

to embrace Islam in January

1986

R – L: Brother Bilal

(Alexander) Dawia, Brother

Lavi-Ali |

First Papua New Guinean

Family to embrace Islam

Brother Barrah Islam (Nuli),

Sister Fatima (Margaret) –

daughter Hajrah missing

|

|

Second Papua New Guinean

family to embrace Islam

Brother Yaqoob Amaki, Sister

Khadijah and their son Ishaq |

Some of the early Muslims of

Papua New Guinea with a

Bangladeshi brother

R – L: Brothers Yusaf

Salmang, Barrah Islam,

Yaqoob Amaki |

|

Some ladies relaxing after a

party

L – R: Sisters Khadejah,

Fatima, Laila, Ayesha, Nasim

Afzal |

Some brother relaxing after

a picnic outside Port

Moresby Museum

R – L: Brothers Umar Nabai,

Barrah Islam, Afzal Choudry

and Muhammad Noor

|

|

Brother Yaqoob Amaki

enjoying with the children

after a picnic

Outside the Parliament

Building in Port Moresby |

First visit of Brother

Mahathir Mohammad to Papua

New Guinea – 1983

before Registration of the

Islamic Society of Papua New

Guinea

L – R: Mr and Mrs Mahathir

Muhammad, Mr and Mrs

Mohammad Afzal Choudry |

|

Some brothers relaxing after

Eidul Fitre party

R –L: Brothers Al-Tayyeb,

Muffakharul Islam, Afzal

Choudry, Ilyas

|

Some brother chatting after

a dinner

R – L: Brothers Azzemullah,

Zubair Afzal, Barrah Islam

and Mohammad Noor |

|

Second visit of Brother

Mahathir Muhammad after

registration of ISPNG –

1985. Standing L – R:

Mohammad Afzal Choudry, Mr

and Mrs Kumarud Abu –

Malaysian Ambassador And a

new Revert to Islam |

Papua New Guinea

delegation (first row, left)

at a conference

“Muslim Women in

Development” Held at Kuala

Lumpur, Malaysia in 1981 |

Imam Mikail Abdul Aziz

testing a child who recently

has completed recitation

Of Al-Qur’an |

Informal chatting after a

dinner: Brother Sadiiq

Sandbach in the middle |

L – R: Brothers Khalid

(Mark) Islam Apai, Mohammad

Afzal Choudry and Amino |

Brother Akbar Muhammad

(middle) with his colleague

(left) and Brother Barrah

Islam |

|

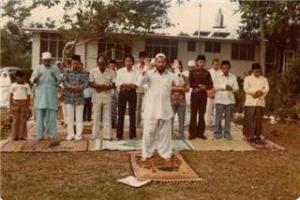

PNG Muslims performing

Salaatul Eid in 1982 |

The Mosque and community

centre in the capital city

of Ports Moresby,

Built in mid 1990s |

|

The praying area for men |

The praying area for women |

|

The Muslim community of Port

Moresby outside the Mosque

And community centre |

At that time in POM there were about

eight Muslims. Amongst them were Br.

Aitiqaad Hussain from Pakistan,

Noorul Amin from Bangladesh,

Tawwakul Hussain from Pakistan,

Ilteja Hussain from India, Shaukat

Noor Khan from India, Ahmad Badwi

from Sudan, ‘Umar from Egypt and

myself, Mohammad Afzal Choudry from

Pakistan. We were worried about the

Islamic education of our children

and after a meeting decided to form

a group to start our children’s

Islamic education. Funds were needed

for the teaching materials and books

etc, which included books for our

own selves to improve our

understanding of Islam as well.

After a while it was decided that a

proper society to keep the records

of funds straight etc would be a

good idea. Dr Ashfaq’s request was

considered and a constitution was

drawn with the first election held

in March 1981. Brother Ahmad Badwi

from Sudan was elected as President,

Brother Noorul Amin from Bangladesh

as Vice President, I as Secretary,

and Brother Shoukat Noor Khan from

India as Treasurer. An application

for the registration of the society

was lodged with the Registrar

General’s office in April 1981 and

my interview was aired on PNG radio;

a television station did not exist

at that time.

Same year opportunity arose for the

participation of Papua New Guinea in

an international conference on

“Muslim Women in Development” at

Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia which was

organised by RISEAP – Regional

Islamic Dawah Council of South East

Asia and Pacific. As no native women

had yet embraced Islam, the Islamic

Society decided to send the wives of

two expatriate brothers. This event

introduced the Islamic Society of

Papua New Guinea to the outside

world for the first time.

It was around this time that Brother

Sadiiq Sandbach – a Scottish

national and retired Colonel –

rejoined the University of Papua New

Guinea and became known to me. There

was an issue with lack of room in

other departments at the University

and Brother Sadiiq Sandbach asked me

if he could use some of the space in

my department (Computer Services),

to which I agreed. So he brought

along with him a desk and a chair

and put it in the corridor, outside

my personal office. We used to see

each other several times a day and

restricted ourselves to the exchange

of formal greetings only.

One day he saw a copy of Al-Qur’an

in my hand and seemed to recognise

it asking me in an excited manner if

I could tell him something about

Islam. He told me that he had always

had the desire to learn about Islam

but could not find anyone to help

him in this regard. He also

mentioned that he once went to a

mosque in Indonesia but people

instead of welcoming him in the

mosque, stared at him suspiciously

as though he was a spy. This made

him very embarrassed and he never

entered another mosque after that.

Over a short period of time we

became good friends and I started

inviting him to my house to discuss

Islam. During this period we also

started discussing the affairs of

the Islamic Society of Papua New

Guinea (ISPNG). He always took a

great interest in ISPNG and became a

sympathiser of sorts, though he did

not embrace Islam until October

1982.

After some months the ISPNG received

a letter from the Registrar General

informing that its registration had

been challenged by the then Justice

Minister – Mr Paul Torato – in his

personal and private capacity, and

not as a Justice Minister, without

providing any reasons. We all got

quite upset and when Brother Sadiiq

came to know about it he suggested

we should personally contact Paul

Torato and to request him for the

reasons. I rang his office and he

personally answered the call. I

asked him for an appointment to

which he enquired why I wanted to

see him. I told him that it was

about the registration of ISPNG, and

he offered me an appointment for the

following day. Brother Sadiiq and

brother Shokat Noor Khan went with

me.

We were warmly welcomed by Paul

Torato personally and he himself

made coffee for us. When we told him

the purpose of our visit he replied

quite bluntly, “what will you do if

I do not give the reasons?” We were

disappointed by his attitude and

told him we would not do anything,

but it was an ethical and legal

requirement on his part to provide

the reasons. He did not answer and

without any further dialogue we left

his office. After a few months we

hired the best solicitor in POM who

belonged to the Jewish faith and

took the matter to court. In the

very first hearing the Judge ordered

the Registrar General to present us

with the reasons for objections

raised by Mr Paul Torato within four

weeks. These were hand delivered to

me in my office in the University of

Papua New Guinea on the last day, at

4 p.m.

The objections to the registration

of our Islamic Society given by the

then Justice Minister included that

Islam is in contradiction to the

constitution of Papua New Guinea; it

teaches extremism; it is an immoral

religion and if allowed it will

cause conflict amongst the people of

that country. We started inviting

Islamic workers from around the

world to assist us with the

appropriate responses to these

objections as we felt we were not

equipped for that purpose. We did

not receive much of a positive

response and were disappointed.

The then ISPNG President, Ahmad

Badawi was acquisition Librarian at

the University Library and I was

Computer Manager, so we started

buying reliable books on Islam,

written by Muslim scholars. One day

I borrowed a book and without

reading it passed it on to brother

Sadiiq. After reading the book,

brother Sadiiq raised some questions

which I was unable to answer. From

then on I started reading all the

books before passing them on to

brother Sadiiq. This increased my

knowledge of Islam which existed on

a more superficial level before. It

turned out Brother Sadiiq helped me

to indirectly increase my knowledge

of Islam and education.

Brother Aitiqaad Hussain used to

lead the Friday prayers and he left

after finishing his contract with

the UNDP in mid 1981. On his

departure we needed a new Imam but

no one was willing to take up this

honourable position and duty.

Finally I accepted it reluctantly. I

felt my knowledge of Islam was poor

and lacking and had never taken on

such a role in my life before.

Initially it proved to be a very

difficult task for me, however

slowly I became comfortable with it.

I started printing Salaat timings

for distribution at the beginning of

each month. I also started typing

and making copies of my Friday

Khutbah for distribution at the end

of each Friday prayer.

On February 2, 1982 the then Prime

Minister – Mr Julius Chan – said

over the radio that he would never

allow Islam to exist on the soil of

Papua New Guinea and that he would

oppose it with all of the powers

available to him. I got upset and

mentioned the broadcast to Brother

Sadiiq. He suggested I write a

letter to the Prime Minister, asking

him for an audience in order to

clear all the misunderstanding about

Islam he had. In fact Brother Sadiiq

drafted that letter himself and gave

it to me for signing and posting,

which I did. Soon I was contacted by

the Prime Minister’s Media Advisor –

Robin Osborn – an Australian

national. He wrote to me saying that

my letter had been forwarded to him

and as the matter had the potential

of getting out of hand he wanted to

talk to me over the telephone. I

rang him and an appointment was made

which was attended by him and most

members of ISPNG.

Mr Osborn said that the Prime

Minister had no knowledge of Islam

whatsoever, and believed it to be a

branch of Hinduism, and many of his

Cabinet members were Christian

priests who were completely against

Islam. He also mentioned that he was

writing a report on Islam for the

Prime Minister and hoped that things

would improve. He also asked me if I

was aware that the CID police were

following me wherever I went to

which I said no. He continued that

the government was fearful of PNG

Muslims and considered them to be

the agents of Ayatullah Khumaini of

Iran and Mu’amar Gadafi of Libya. He

also informed me that all my mail

was scanned. I replied that I had

never suspected any of the things he

had revealed to me neither that I

was indifferent as we were not doing

anything against the interests of

the country. However after a few

months the government was changed

and Michael Somare became the Prime

Minister, once again.

It was middle or late 1982 when the

Malaysian Prime Minister, Brother

Mahathir Muhammad visited Papua New

Guinea for one day, on his return

from the Commonwealth Head of States

meeting in Fiji. Michael Somare, the

Prime Minister of PNG was his

personal friend and forced him to

stop over in Port Moresby. I met

brother Mahathir and asked him to

recommend the registration of our

Islamic Society to Michael Somare.

He told that he was just returning

from his office and had already

discussed the matter with him, as he

was instructed by Brother Tanku

Abdur Rahman, the ex-Prime Minister

of Malaysia and President of RISEAP,

to do so. He advised me that we

should not confront the government

as this was not the way to achieving

the success we wanted. He also

advised me that we should keep a low

profile and wait for the right time

for the registration of ISPNG. He

mentioned that Michael Somare had

promised him the registration once

the priests of his cabinet had

calmed down. Before leaving PNG,

Mahathir Muhammad invited Michael

Somare for the state visit of

Malaysia, which he accepted.

Brother Sadiiq read a lot of

literature on Islam for about six

months and we had many heated

discussions. One day he asked for a

copy of my Khutbah. I started giving

him a copy of it every week which we

would discuss afterwards. After a

few weeks he asked me for a copy of

the Salaat timings. I asked him in a

delighted and excited manner if he

was a Muslim. He replied that he was

not a Muslim yet. He explained that

he had studied almost all the

religions of the world, including

almost all the denominations of

Christendom, and found Islam to be

the perfect faith in line with the

human nature and in perfect tune

with the human intellect. He further

added that he would only embrace

this religion if he was able to

perform the five daily prayers.

Fasting was not a problem for him as

he had tried it and found it quite

easy. I asked him that when he was

totally satisfied with his

understanding of Islam and ready to

embrace, he could let me know. Only

a couple of weeks had passed and he

came to me and asked if he could

join us for Friday prayers. The

following Friday he joined and we

went for the prayer and he said the

Shahadah. It was October 1982 and he

was the first person to declare

Shahadah on the soil of PNG – Allahu

Akbar, Allahu Akbar, Allahu Akbar!

In 1983 Brother Shafiqur Rahman from

Sydney visited Port Moresby and Lae.

At that time he was working for

Darul Ifta and came to assess the

possibility of a grant to Papua New

Guinea in order to purchase some

property for the purpose of an

Islamic Centre. After completing his

findings he gave us an application

form to complete (the society was

not then registered). He promised to

recommend, but without a guarantee,

an amount of US$20,000 for PNG

Muslims; this was not accepted as

being peanuts for the set purpose.

During the same or following year

Sheikh Muhammad bin Qu’ud of Darul

Ifta, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia also

visited Port Moresby with one of his

colleagues. Promises were made but

left unfulfilled; the small number

of Muslims amongst which there were

no natives may have been the reason

for that.

One Friday during 1983, a Muslim

brother from Bangalore, India

(unfortunately I have forgotten his

name) attended the Friday prayers.

He was on a business trip to buy

some timber. After the Salah he took

me into a corner and asked why we

had not considered buying a place of

our own which would be neutral

ground for Islamic Da’wah

activities. I told him that we did

not have enough money to do that. He

gave me US$10,000 in hard cash and

wished every success for us and our

Islamic Society. This was the first

major donation and the first

building block towards the

establishment of Islam in Papua New

Guinea – may Allah Ta’ala reward

that brother abundantly in this life

and in the Hereafter. We never saw

him again.

It was December of 1983 when I

received a telephone call from the

Secretary of Justice department, Mr

Luke Lukas – a naturalised citizen,

originally from Holland. He asked me

if I could see him straightaway. I

excused myself explaining I was busy

and asked if the following day was

okay, to which he said it was

regarding the registration of the

Islamic Society. He also mentioned

that Michael Somare was going on a

State Visit to Malaysia in four days

time and they had to discuss and

finalised the matter before his

departure. I went to his office and

found him waiting for me with the

Secretary of Foreign Affairs and

Registrar General. He welcomed me

and explained the urgency of the

matter and asked the Registrar

General for a quick decision –

whether it was a registration or a

rejection, but not without valid

reasons.

The Registrar General mentioned that

he did not understand some of the

words used in the constitution of

the society, such as Quran and

Hadith. He also objected to one of

the clauses of the constitution

which stated that in the event of

dissolution of the society its

assets will be transferred to the

AFIC (Australian Federation of

Islamic Councils). He was not happy

about the transfer of PNG moneys to

any other country. I offered to

replace the statement with the

transfer of funds to some charity

organisation within PNG, to which he

agreed and asked me to bring the

revised constitution to his office

the following day.

It was Friday and I went to the

Office of Registrar General after

Juma’a prayers with the amended

constitution. He served me with a

cup of tea and signed all the pages

of the constitution without delay

and without reading anything, and

asked his secretary to prepare a

certificate of Registration

straightaway. I had the certificate

in my hand within half an hour and

instantly rang Sadiiq Sandbach

informing him that our Society had

been registered. He could not

believe it to which I said that the

certificate was in my hand and I was

on way to my office. That day was a

great day for Muslims in PNG and we

celebrated it over the weekend.

The following year we decided to

send Brother Sadiiq Sandbach as our

representative to the Annual General

Conference of the RISEAP (Regional

Islamic Daw’ah Council of South East

Asia and Pacific). We thought that

being a recent Revert to Islam he

would leave a good impression on the

participants and could present our

case in the best possible way. He

was well received and he presented

our case in a beautiful manner which

made all the participants of the

conference very sympathetic towards

Papua New Guinea. During his stay in

Malaysia, the Libyan Embassy staff

contacted him and offered some help.

Brother Sadiiq informed him that the

PNG government considered us as

agents of Mu’amar Gadafi and

Ayatullah Khomeni. So we would

prefer not to bring Libya or Iran

into the picture. They still

insisted they wanted to help and Br

Sadiiq suggested that they could

send us an electronic typewriter and

a photocopying machine, but only

through RISEAP. They agreed to this

and also gave him US$3,000 in cash.

The two items were received by us

soon.

The next step taken was the

publication of a bi-monthly

newsletter under the name

“Al-Islam”. The first issue of

“Al-Islam” was produced in February

1984. One hundred copies were

produced and distributed through the

University Bookshop, free of charge.

The typesetting was carried out by

me and it was edited by Brother

Sadiiq Sandbach. It was printed at

the University Printing Press at a

very nominal cost. Being staff

members we paid the cost of the

paper and ink only. The newsletter

was printed up until the end of 1988

and then stopped due to unavoidable

circumstances. The number of copies

published increased with each issue

and 800 copies were published for

the last issue. After the

publication of the second issue of

“Al;-Islam”, the University

Chaplaincy launched its Christian

newsletter in competition. They

managed to publish only one issue

and it was not seen again.

The year 1984 was a very lucky year

as we welcomed three great Muslims

of our Ummah – Brother Eltayyeb

Abdul Aziz Eltayyeb from Sudan who

joined UNDP as Commissioner for the

refugees, Brother Azeemullah, an

engineer from Fiji who joined Shell

PNG on an exchange programme and

Brother Shahul Hameed from Malaysia,

who joined a private retail company

as an accountant. All three brothers

were practising Muslims with an

in-depth knowledge of Islam and

possessed good experience in Dawah.

This boosted our morale and

activities in the field of Dawah

increased many fold.

It was towards the end of 1985 that

we published an article on the

prohibition of Alcoholic drinks and

the eating of pork in Islam. The

article was well received by the

university population. I received a

letter from one of the Students,

Alexander Dawia who was in his final

year of B.A honours in history. He

was very impressed by the article

and asked for more information and

showed an interest in joining the

Islamic Society. I wrote him to see

me and we had a few meetings and

discussed Islam. I also introduced

him to the Ahmad Deedat videos which

were very popular at that time. The

first video he watched at my

residence was about “What the Bible

says about Muhammad?” It interested

him so much that he kept taking

notes. I told him to watch it at his

leisure and that I would give him a

booklet of the video before he left.

Sometime in November 1985 Alex went

to Australia to do research on Black

Theology. He asked me if he could

stay with some Muslims to learn more

about Islam. I contacted Qazi Ashfaq

Ahmad who had by that time left the

University of Technology and had

gone back to Sydney to settle down.

Dr Ashfaq Ahmad contacted various

mosques along the coast, from Cairns

to Sydney, and made a pleasing

itinerary for him. In January 1986

Alex arrived in Sydnet and Brother

Ashfaq looked after him as a guest

at his own residence.

One evening Brother Ashfaq Ahmad

rang me and asked to have a word

with Alexander. Alexander told me

that he had decided to say Shahadah,

but he wanted to do it in Port

Moresby in my presence on his

return. I told him there was no need

to delay it and that he should do it

since he had made the intention. The

following day was a Friday – 16 or

18 of January 1986. Alaxander Dawia

pronounced the Shahadah at the Jamia

mosque in Sydney. The white Muslims

were introduced to him and they

greeted him pleasantly inviting him

for meals, Alexander thought their

behaviour was strange and out of

character as the White expatriates

in PNG never invited the black

locals into their homes, in fact

they were rarely even nice to them.

Alexander Dawia being from

Bouganville (the Solomon Islands)

was very dark so we suggested him

the Muslim name “Bilal” explaining

the full background of the first

Bilal – may Allah be pleased with

him – who was a distinguished

companion of our beloved Prophet

Muhammad – may peace and blessings

of Allah be upon him.

In the mean time Brother Sadiiq had

been discussing Islam with Lavi-Ali

who was his adopted son. When

Lavi-Ali learned about Alexander’s

decision he also decided to

pronounce the Shahadah on the same

day. In this way the Islamic Society

of Papua New Guinea witnessed the

reversion of two native Papua New

Guineans who received the honour of

being the first native Muslims. In

February Alexander returned to Port

Moresby and asked if he could stay

with some Muslim brothers as his

whole family consisted of staunch

Christians. He felt uncomfortable

staying with them now. Brother

Azeemullah’s family was in Fiji and

as he was alone he offered his house

to Bilal. Azeemullah helped Bilal to

memorize Salah within a few days.

Sometime later there arose an

opportunity at the RISEAP for

someone to attend a conference and

Bilal was sent to take part. On his

arrival he made the headlines in

Malaysian newspapers as the first

Muslim of Papua New Guinea. The

respect he received in Malaysia was

enormous as wherever he went people

recognised him and requested his

company inviting him to sit and dine

with them. On his return another

opportunity arose at the Islamic

University of Islamabad, Pakistan

for the training of new Imams. Bilal

participated in that and made many

contacts in Islamabad. He met a

brother from Tablighi Jam’at who

took him to their headquarters in

Raywind, Lahore. Through Tablighi

Jam’at Bilal visited India,

Bangladesh and Sri Lanka in the six

months that followed. After

obtaining his degree qualification

he found a job in Australia and

settled there.

I was living in the University

campus but would go to my office in

my car and on my way to home. I had

the habit of offering a lift to

anyone that was walking; it was

mostly the Papua New Guineans who

would be on foot. One day I gave a

lift to a Librarian cataloguer,

Barrah Nuli. Sitting next to me he

asked me if I was the one who was

publishing “Al-Islam”. I replied yes

and he requested a copy of the last

issue which he had unfortunately

missed. I went with Bilal and took a

copy of the issue to his office and

introduced him as a new Muslim.

Barrah was delighted to meet him and

mentioned that he was also very much

inclined towards Islam as was his

wife who was working in a bank. I

introduced him to Brother Azzemullah

who started taking Barrah’s family

to his house for the weekends and

showed them videos and discussed

Islam. Towards the end of 1986

Barrah and his family also embraced

Islam. His wife Fatima was the first

Papua New Guinean lady to embrace

Islam and his daughter Hajira the

first child. Sister Fatima’s father

was a Church Minister, who strongly

opposed their decision of reversion

to Islam. When he realised that they

would not change their decision at

all, he agreed to their reversion.

One of Barrah’s friends by the name

of Mr Salmang also became interested

in Islam through Barrah and ended up

becoming a Muslim in early 1987. His

wife was a very staunch Catholic but

also embraced Islam after a year.

She was followed by Umar Nabai,

another cataloguer in the University

Library and Khalid Islam Apai – the

National Boxing Champion, who was

working as a regional Works Manager

with the Department of Work and

Supply. All of the early Muslims

were graduates and professionals and

started taking part in Dawah

activities straightaway after their

reversion, and as a result the

number of new Mulsims gradually

increased.

Brother Azeemullah was very active

in Dawah after his arrival in PNG

and would discuss Islam with his

personnel manager Mr Amaki. Amaki

initially refused to listen to

anything about Islam but gradually

started talking about the concept of

God. Brother Azeemullah who had

brought several videos of Brother

Ahmad Deedat with him from Fiji,

invited Mr Amaki to watch some of

them, to which he agreed. Mr Amaki

and his wife, a banker started

watching these videos and soon they

decided to pronounce their Shahadah.

Brother Ahmad Deedat’s videos became

very popular and for their wide

circulation we decided to make some

copies of them. The university had

an Audio Visual section and I

approached its staff for this

purpose. Two staff members of the

section started to watch the videos

while copying them. I started

visiting them regularly to discuss

what they had watched. Brother

Wanjemanker (may be wrong spelling)

began discussing Islam with me quite

regularly; whenever he had some free

time he would come to my office and

occasionally to my home which was

only a few doors away from his

residence. After a few months I

asked him politely if Islam had

penetrated his heart, to which he

answered “Yes”. The following Friday

he pronounced his Shahadah and chose

the Muslim name “Jaffar” as his own.

It wasn’t long before his colleague,

after becoming convinced, also

joined the fold of Islam with “Abid”

as his Islamic name.

Brother Jaffar’s wife was a staunch

Christian and had always disliked

his reversion to Islam. Because he

was a very calm, mature and humble

person, he handled the situation

wisely. He had five children at that

time, two girls and three boys. He

started bringing his boys to the

children’s Islamic classes and gave

them Muslim names. On the Eidul Fitr

that followed I decided to visit

Brother Jaffar and his family to say

“Happy Eid”. With me was my wife and

we took some sweets for his

children. As much as he was happy to

see us, his wife did not share the

same sentiments and swiftly

retreated into her bedroom locking

it after her. Brother Jaffar

requested her to come out but she

argued with him in their native

language. Judging the facial

expressions and body language of

Brother Jaffar my wife and I

strongly agreed that it was

appropriate that we leave the scene.

We gave the sweets to his children

and left.

Brother Jaffar’s wife tried her best

to force her husband to denounce

Islam but he refused – the more she

pressured him the stronger his Imaan

became. Finally she personally went

with a complaint to the Vice

Chancellor of the University that I

was propagating Islam through my

office, and that it was important

that he stop it. The Vice Chancellor

conducted inquiries into this matter

but did not find any evidence for

it. I received this information

through one of my staff members

after he had been summoned by the

Vice Chancellor in this regard.

Brother Jaffar was senior in age

amongst all the Reverts and a few

years older than me. He was very

enthusiastic about learning the

Arabic alphabet and the recitation

of the Quran. He worked hard to

learn the Arabic language and would

always ask me for the possibility of

an English Arabic dictionary from

somewhere; however at that time

there weren’t any available. A few

years after my leaving PNG, brother

Jaffar retired and went back to his

village to settle down; there he

started Da’wah amongst his own

people. We stayed in contact for a

long time and in his last letter he

wrote about the death of his wife. I

understood that she had never

accepted Islam, may Allah Ta’ala

give her the least punishment for

what she did in her worldly life.

All his children are very good

Muslims.

The Papua New Guineans were well

known for being very heavy drinkers;

it was discussed among the members

of the ISPNG how this issue could be

tackled, acknowledging the fact that

it would be difficult for them to

stop drinking straightaway after

their reversion to Islam. Brother

Abdullah Gurnah of Zanjebar

(Tanzania) suggested we should

perhaps not mention the prohibition

of alcoholic drinks to them

straightaway. Once they had settled

into their new religion the issue

could be raised with care. I

disagreed and told that we were not

doing the work of Da’wah for the

benefit of our own selves, we were

doing it for Allah and Allah alone,

and so we MUST not worry about

anything at all, and we should

follow the guidance of our beloved

Prophet Muhammad (SAW) strictly.

Allah blessed the new Muslims

greatly as they never again consumed

alcohol or ate pork once they had

pronounced the Shahadah. It was like

a miracle.

The reversion of Khalid Islam Apai

was very interesting. He was on a

training course at Lae Polytechnic.

One of his teachers was from

Pakistan, who used to receive copies

of “Al-Islam” and would pass one on

to Mr Apai. One day I received a

call from Mr Apai, who wanted to

know something about Islam. After

that we talked regularly over the

telephone on Islam, sometimes for

hours. Finally Brother Khalid

pronounced his Shahadah over the

phone and I sent him some literature

and talked to him about praying

regularly. We had never met and one

day he rang me to tell that he was

coming over to Port Moresby and

wanted to visit me. We told each

other what we would be wearing so we

could recognise each other. When we

met at the airport we embraced each

other. The joy and what I felt at

that moment can not be expressed in

words. He stayed in Port Moresby for

a few days and learned the basic

tenets of Islam.

Brother Khalid Apai was married and

his wife was working as an air

hostess with Air Niugini; her father

was a minister of a church. Brother

Khalid earned a lot of money during

his boxing career and bought some

plantations and other property which

was in the name of his father in

law. His reversion upset his father

in law greatly and he tried

everything to win him back, but

Khalid did not retreat an inch from

his stand. Finally Brother Khalid

lost all of his property but he

stood firm in his Imaan. His wife

offered her support at first;

however Allah alone knows what

happened to her as she turned

against Khalid later on. She left

Khalid who loved her a lot and who

put every effort into trying to win

her back but without success. As

problems came his way he became

stronger as a Muslim and his faith

remained unmoved – may Allah Ta’ala

reward him for all the trials and

tribulations he went through.

Finally his marriage was dissolved

and he married again to an Assistant

Secretary of Education at that time.

Brother Khalid is still a valuable

member of ISPNG, as far as my

knowledge goes, he acts as an Imam

whenever Brother Mikail Abdul Aziz

is away.

In 1987, two Muslim brothers from

the United States who were members

of the Nation of Islam came with

their families on a Visit to the

Pacific countries after visiting

Mu’mar Gadafi of Libya. One of the

men known as Akbar Muhammad was a

very close friend of Mu’amer Gadafi

and was well known in the European

and Australian circles because of

his links with Libya. He was refused

a visa to enter Australia, but

somehow he got a visa for PNG and

requested me to see him. He was

staying at a hotel and I went to

visit him with two of the new

reverts with me. While talking on

various issues, the time for Maghrib

prayer arrived and I said that we

wanted to get ready for it. By that

time Barrah had learned all of the

Salah by heart with a few short

Surahs from Al-Qur’an, so I asked

Barrah to lead the prayer. Initially

he showed some hesitation and I

offered encouragement by telling him

he could perform the duty easily and

successfully, after this he led the

prayer. At the end of the Salah

brother Akbar Muhammad stood up and

started affectionately hugging

Barrah over and over again. Then he

asked me how he had learned the

Salah in Arabic as they (the people

of the Nation of Islam) were still

praying in English. I was shocked to

learn what he had revealed.

When the Australian government came

to know that they had been granted a

visa by the PNG government there was

a great hue and cry in the national

papers, both in Australia as well as

in Papua New Guinea. One evening I

invited them for a dinner at my

residence and somehow it came to the

notice of the media in PNG. The

following day there were headlines

about them and our links with Libya.

The Archbishop of Port Moresby gave

very hostile statements to the media

against Muslims in PNG. He bluntly

asked why the government had

employed Muslims in the University –

were they there to teach students or

propagate the religion of Islam!

After this incident the prejudice of

the churches reached new heights in

their hostility towards Islam. I

remember we compiled a very basic

article on Islam, about four A5

pages and wanted to get it printed.

The printing press in Port Moresby

was owned by the Catholic Church and

they absolutely refused to print it,

though we agreed to pay any charges

for it.

After the reversion of a good number

of Muslims, we set about planning

social activities and events such as

picnics and the visiting of various

places of interest in Port Moresby.

At the same time a women only circle

was also started which was well

attended. It provided the chance for

local revert ladies to mix with the

expatriate Muslim women to not only

learn more about Islam but also

share skills such as new cooking

recipes etc, and it was an

opportunity for the children to get

to know and play with each others.

Wherever we went we never missed our

Salah, we would pray at the correct

time in Jama’ah. We had prayed Salah

at almost every public place in Port

Moresby – outside the museum, in the

national park, outside PNG

Parliament, at the beach and other

public places etc. When we prayed

the local people would gather around

us and watch with surprise and

wonder at what we were doing. On

such occasions we would ask one of

our local brothers to explain to

them in their language what the

prayer and Islam meant. This was a

good way of Daw’ah. During the same

year the first Tablighi Jama’t came

from Australia for a week. It was a

good mix of different nationalities,

mainly Malaysian, Singaporeans and

Australians.

Looking at the increasing number of

new Muslims we began to think about

neutral premises appropriate for

praying and from where we could

disseminate the teachings of Islam.

Brother El-tayyeb mentioned to us a

friend by the name of Dr. Ahmad

Totonji who could help us in

establishing an Islamic Centre. One

evening brother El-tayyab invited

all Muslims for dinner after which

he rang Brother Ahmad Totonji,

however he was resting. We got

through to him around midnight and

explained our plans to him. Brother

Totonji agreed to finance 50 per

cent of the total costs – whether we

bought or rented the place. In

addition to that he promised to

provide the salary for an Imam. He

said that 50 per cent of our share

would make us feel proud to be the

owners and this would ensure that we

would take good care of the

property. Everybody was highly

pleased and happy and we looked

ahead at a great future for Islam in

PNG.

Brother Totonji was so sincere,

truthful, and keen and interested in

our religious affairs that he sent

an Imam from Australia within a

couple of months after our telephone

conversation; his name was Yusuf

Popat and he was originally from

Afghanistan. Brother Totonji left

the selection entirely on us. We

called a general meeting and

explained everything to the

participants. Since there was no

place purchased or rented yet,

people were a bit hesitant and did

not know where Brother Popat should

be housed. PNG was one of the most

expensive countries at that time and

we felt it was appropriate to wait

until we had a place. I believe that

Brother Yusuf Popat was not happy

with the general environment of the

place during his visit to PNG.

We began looking for a house which

could be converted into a mosque to

start with, as the property prices

were at an all time high – the real

estate business was very hot.

Fortunately a house became available

on the market owned by Air Niugini

and its price was PNG Kina 65,000 (1

Kina = US$1.40 at that time). We had

about 12,000 Kina at that time out

of which 10,000 Kina was paid for

the deposit with a promise to clear

all the payments within 6 months. 50

per cent of the share came

straightaway from brother Totonji

and we started raising the rest

locally and internationally. A

donation appeal was drawn by Brother

Mohammad Shamsul Alam Chowdhury, the

then President of ISPNG, fully

documented with action and future

plans. The response was good, both

locally as well as internationally.

We were hoping for about $50,000

which was not an easy target to

reach. There were many incidents

that took place which I would

describe as miracles during the

whole exercise; however I will only

mention one.

A copy of our appeal for donations

somehow ended up in the hands of a

trainee in a Correctional Institute

in New York, America. He had only

$13 in his account at that time and

the telegraphic transfer charges

were $11. He sent the remaining $2

into our bank account directly which

was overlooked by us. We only came

to know about this fact after

receiving his letter in which he

explained the plight he was in and

how pleased he was to help towards

this cause. He was a new Revert to

Islam and wrote greeting in Arabic.

Generous donations came from Hong

Kong, Pakistani employees of the

Asian Bank in Manila, our contacts

in Canada, Singapore and the UK.

After all the efforts that were put

in and which were spread over 4

months we were still short of

$15,000 and worried in case we lost

our deposit.

In those days the Far East Regional

President of WAMY was Brother

Kumarud-din Noor and I wrote to him

about the difficulty we were facing.

He instantly responded with an

explanation that he didn’t hold a

budget but he would surely forward

our request with his strongest

recommendations to the head office

in Jeddah for assistance and asked

us to have trust in Allah. The story

got interesting later: our request

was forwarded and it was lying on

the table of the General Secretary

when a generous brother came and

asked about it. The General

Secretary explained the whole matter

to the enquirer who in turn took his

cheque book out and wrote a cheque

for $15,000 and asked for the letter

to be destroyed. In this way in six

months we were able to raise $10,000

more than what we needed.

The house was purchased and we

started to make use of it. This

centre was in the Corobosea area

which was not very good from the

security point of view. In reality

there was no safe place in Port

Moresby from the security point of

view. There had been some trouble

from the neighbours – an Australian

family – in the beginning. Whenever

we called Adhan the neighbours would

put on radio at its full volume.

However things settled down soon. We

started various study Halaqahs to

learn about Islam. Brother El-Tayyeb

started teaching Arabic to the new

reverts and children. Other

activities were also started which

included Dars-e-Quran (Quranic

tafseer) and social activities. 1987

saw the departure of Brother

Azeemullah and 1988 the departure of

Brother El-Tayyeb and we lost two

great Muslims and Da’ees of Islam.

During this period some Bangladeshi

Muslims joined us and the overall

population of the Muslim community

increased.

Brother Tontonji recommended Mikail

Abdul Aziz to us as an Imam – he

only put the recommendation forward

and left the entire decision to us.

We looked at his qualifications,

post graduation from Medinah

University, and decided to appoint

him. He joined us on 2nd July 1989,

and the proper Daw’ah activities

began in the centre. Brother Imam

started Quranic clasees, Islamic

quiz programmes and Islamic classes

for the children. A Halqah was also

started by Brother Imam in my office

at the University of PNG on

Wednesday evenings as majority of

the Muslims were living in Waigani

area that was a bit far from the new

centre. Islamic lectures were also

delivered at University of Papua New

Guinea, Administrative College and

Port Moresby International high

school by Brother Shahul Hameed and

by me. This followed publication of

four booklets written by me: “What

Islam is all about”, “Islam and

Papua New Guinea”, “The Revelation

of Al-Quran and its Preservation”,

and “Is Christianity a loving

religion?”

Brother Mikail Abdul Aziz had good

contacts in Saudi Arabia and asked

Medinah University to give admission

to some of the Papua New Guinean

youth. A delegation from the

University came to visit in

1990/1991 and selected a few young

men. The first person to go to study

was Brother Abdul Majeed; however he

was not able to cope and didn’t

return after coming home for

holidays at the end of the first

academic year.

Brother Mikail Abdul Aziz worked

hard at extending the Message of

Islam to the people he came in

contact with. He particularly used

the main market place for this

purpose. The Papua New Guineans were

used to the Christian method of

perks and prizes, so they used our

na´ve Imam on the same level. People

he came in contact with manipulated

him for things such as a cooking

stove and other material objects

including hard cash. The Society

initially released the funds and

when it became a routine exercise

they stopped the payments from going

out to such people. The Imam was

told not to entertain such people.

Brother Mikail Abdul Aziz was so

keen on winning people over to Islam

that he started paying them out of

his own pocket.

Brother M S A Chowdhury, the then

President of ISPNG was working with

the Civic Centre and applied for a

piece of land for a Muslim Cemetery

which was granted. We also started

applying for a bigger place for a

proper Mosque but faced very strong

opposition from the Churches. Each

time an application was made for an

advertised place the Churches joined

hands and came in the way of our

success. Finally Brother Mohammad

Yusuf, the then President of ISPNG

with the help of Malaysian High

Commissioner met the Minster of

Lands directly – I believe it was Mr

Hugo, a naturalised citizen

originally from Holland – and he

kindly allocated us a three and half

acres of land at Hohola where our

present Islamic Centre stands. All

the architectural work was carried

out by Brother M S A Chowdhury, who

was a civil engineer. Brother Yusuf

also contributed a lot during his

term of Presidency. He made the

Mimber, book shelves and glass

cabinets for the old centre as he

knew the basic carpentry.

Soon after the people from Mendi and

Chimbu provinces started embracing

Islam and a decision was taken to

make regular trips to the Highlands.

Brother Mikail Abdul Aziz and

Brother Yaqoob Amaki, and at times

Brother Sadiiq Sandbach would go and

dozens of people would embrace Islam

on each trip. The behaviour of

people changed as a result and this

contributed to the improvement of

law and order which was a big

problem in the Highlands. A time

came when the Chief Minister of the

Highlands told the Muslim da’ees to

convert more and more people to

Islam as they were becoming better

citizens. He once, before going on a

trip, gave the keys of his house to

Brother Imam and told him to

consider it as his own house in his

absence. He never embraced Islam

during my stay in PNG. The modest

centres were established there with

modest financial help from the

Society.

On the 20th of April 1992 I left

Papua New Guinea for good, a hundred

people belonging to the local

population had reverted to Islam

during the 12 most memorable years I

had spent there. I found the local

Papua New Guineans very

understanding, cooperative and

helpful. Whatever we needed anything

we would just ask for it and we got

it with the least of problems. I

remember an incident which is worth

mentioning. In 1989 we went to an

agricultural show and at one of the

stalls we came across some spices.

It was always difficult to find

spices in PNG and we would normally

bring them from Singapore/Hong Kong

or import them from Australia. I

asked the stall attendant if it was

possible to buy some. He politely

answered that they were not for sale

but that if I left my address with

him he could try to deliver some at

the end of the show. A couple of

days passed and he appeared on my

doorstep with an impressive variety

of spices including vanilla sticks.

Showing him how pleased I was I

excitedly enquired about the prices

at which he was selling them. I

still remember his facial expression

that conveyed to me the message that

I seemed to have asked him a foolish

or silly question. He replied very

politely that they were free as he

had told me they were not for sale,

and he had come by as he had

promised just to give me some. He

said he could not accept a hot or

cold drink and left with the excuse

that he lived at a good distance

from my house and had to leave as

daylight was short.

Mohammad Afzal Choudry

1st March, 2008

e-Mail:

afzalchoudry@hotmail.com

ADDEDUM

I would like to add the course of

events that led us to the occurrence

of the availability of Halal meat

and poultry. In 1980 after arriving

in Papua New Guinea we learned that

there was not a single source of

Halal meat or poultry. Initially we

began buying meat and poultry from

the available Christian shops;

however, towards the end of 1980 we

started buying live chickens and

butchering them in the backyards of

our homes so that we could enjoy

Halal food.

Following on from this we decided to

see if we could buy goats and/or

sheep in a similar way so as to

bring home and slaughter in order to

adhere to Muslim dietary laws. There

were no sheep in Port Moresby and

during my 12 years in PNG I had not

seen a single sheep anywhere in the

capital. Some local people informed

us that goats were available from

nearby villages. We would then drive

for hours from one village to

another in search of them. Finally

we found around three villages which

had a few goats. We began buying

live goats from these villages,

transporting them back to our homes

in our car boots and slaughtering

them in the backyards of our homes

as we did with the chickens! A

little over a year had gone by and

the stock in the villages had been

drained.

It was in 1981, on the occasion of

Eidul Adha, when we decided to make

arrangements for the sacrificial

slaughter of a cow. This was the

first Qurbani (sacrifice) to take

place on such a scale on the

festival of Eidul Adha in Port

Moresby. Five Muslim families

decided they would contribute

towards sharing a cow if such an

opportunity arose. The manager of an

abattoir, which was about 15 miles

out of town, was contacted and

explained that the sacrificial

slaughter was being celebrated as a

commemoration of Prophet Abraham’s

willingness to sacrifice his son, as

commanded by Allah, The Most High.

We narrated this event in detail and

told him that he might have read it

in his bible.

We also emphasised that in order to

celebrate the festival in the purest

way we would want to slaughter the

cow according to Islamic tradition –

without shocking the cow to a

senseless state – to which he

agreed. Eidulul Adha that year

happened to fall on a weekend and we

came to an agreement to pay his

staff any overtime for slaughtering

the cow on the Sunday; however he

refused to accept any payment for

his own self.

The abattoir housed cows on its

premises and we were told we could

select any one of the ones we had

seen. In some brave cases wives and

children went along and collectively

the families chose a spotless white

cow, healthy and strong looking

adorned with big horns that were

shiny and beautiful. What follows is

a somewhat unconventional account of

how the events occurred: four local

Papua New Guinean workers began

chasing the cow taking them well

over an hour to catch it, control it

and direct it towards the abattoir.

They produced sufficient rope with

which they tied the legs and then

put her down on the ground. The most

senior Muslim brother amongst us,

Brother Aiteqaad Hussain was

assigned the duty to cut the throat

of the animal with a loud Takbeer.

The blood came gushing forth when

all of a sudden the cow with all of

its force and might stood up leaving

the four locals speechless and

helpless. Despite the big scare the

animal was brought under control and

the ritual was completed.

The manager of the abattoir was

clearly affected by the experience

but did not utter a word to us. The

cow was skinned, cleaned and cut

appropriately so that the shares

could be distributed. We left for

our homes pleased we had made

contacts with the abattoir manager,

and secure in the knowledge that we

could go back if and when our

requirement for Halal beef came up

again. A few months passed and we

went back, however the manager told

us politely that he could assist us

again but not in the manner of the

slaughter that took place the first

time. He made it clear he could lose

his job and a compromise was

reached.

From 1986 onwards arrangements with

private farms were made for the

slaughter of cows according to the

proper Islamic method. From then we

were involved in the major part of

the whole operation – the

slaughtering, skinning and piecing;

in fact we even purchased tools and

became experts of sorts. I hope this

procedure is still in action like it

used to be.

By 1986/87 the number of Muslims had

increased many fold – not only was

there an increase in the Muslim

expatriates in the country but local

Papua New Guineans started embracing

Islam. The question of enough Halal

poultry came up. The existing method

was thought of as inadequate (still

in back yards and gardens of homes).

Many people did not like butchering

the chickens themselves, and they

felt they were burdening other

brothers if they asked for

assistance.

Sometime later the management of a

poultry farm by the name of Ilimo

Farm was contacted, the only one of

its kind in Port Moresby at that

time, and we asked them whether

there was the possibility of

achieving an Islamic slaughter of

chickens on a large scale. They were

straightforward and made it clear

that they could help us but we would

have to do the butchering ourselves.

It was agreed upon that a couple of

Muslim brothers would go a couple of

hours before the factory opened and

do the slaughtering themselves

whenever Halal poultry was required.

200 to 300 hundred chickens used to

get butchered each time. The method

was such that two brothers from the

Islamic society would go along each

time to say Takbeer on each chicken

before it got butchered. Once the

lot was finished the management

would give them a gap of 30 to 40

minutes before the regular work was

started. By that time the Halal

chickens were sorted through so that

they did not get mixed with the non-halal

ones. The chickens were then packed

in cartons of eight and frozen

before being distinctly labelled as

the property of the Islamic Society.

After a day passed we were able to

buy the number of boxes required,

however the purchase of individual

chickens was not possible. The farm

would contact the society when the

supplies were running out and we

would send someone for the next lot.

The system worked well and without

any confusion.

When the local Papua New Guineans

started embracing Islam they would

require Halal chickens too, however,

like their expatriate brothers most

of them were not in the financial

position to buy a box as the minimum

allowed to be purchased and not all

of them owned freezers. At this

point the Islamic Society decided to

buy a freezer and keep enough

supplies for their local brothers to

buy the poultry as and when the need

arose. Again I hope this system is

still in use.

Source :

http://ispng.wordpress.com/library/articles/my-memories-of-islam-in-papua-new-guinea/

|